Celebrate Dísablót on May 14th

Dísablót, one of the most significant pagan festivals celebrated in ancient Scandinavia, is still remembered and commemorated by modern-day pagans and heathens. This springtime festival, which usually takes place on May 14th, was dedicated to the dísir, the female spirits and goddesses who were believed to protect and bless the fertility of the land, animals, and people. Here, we will explore the history, traditions, and significance of Dísablót.

Origins and Meaning of Dísablót

The word “blót” in Old Norse means sacrifice or offering. Ancient Heathens performed Blót ceremonies to appease the gods and goddesses. Our ancestors sought their blessings and favors, and to ensure the community’s prosperity and protection. Dísablót, therefore, is a special blót dedicated to the dísir. Heathens consider the dísir to be our guardians and benefactors. The term “dísir” (singular dís) refers to ancestral female spirits. These ancestral spirits watch over their descendants and guide them in their daily lives. Eventually, the dísir evolved into a type of goddess, whom we honor.

Our ancestors held Dísablót in the spring or early summer, at the beginning of the growing season. They looked to spring as at time of renewal, hope, and optimism. The harsh winter had passed and the land was ready for planting and harvesting. People invoked and praised the dísir for maintaining fertility. People also prayed to them for protection and guidance in family, marriage, childbirth, and health. Dísablót is a celebration of life and fertility, and a form of ancestor worship.

Dísablót Rituals and Offerings

Not surprisingly, Dísablót practices varied from region to region and community to community. However, this festival had some common elements and themes. People offered food and drink to the dísir. The offerings could be meat, bread, cheese, beer, mead, or other delicacies. People placed the food on a special altar or platform, which they decorated with flowers, greens, and ribbons. The altar became the connection between our world and the dísir.

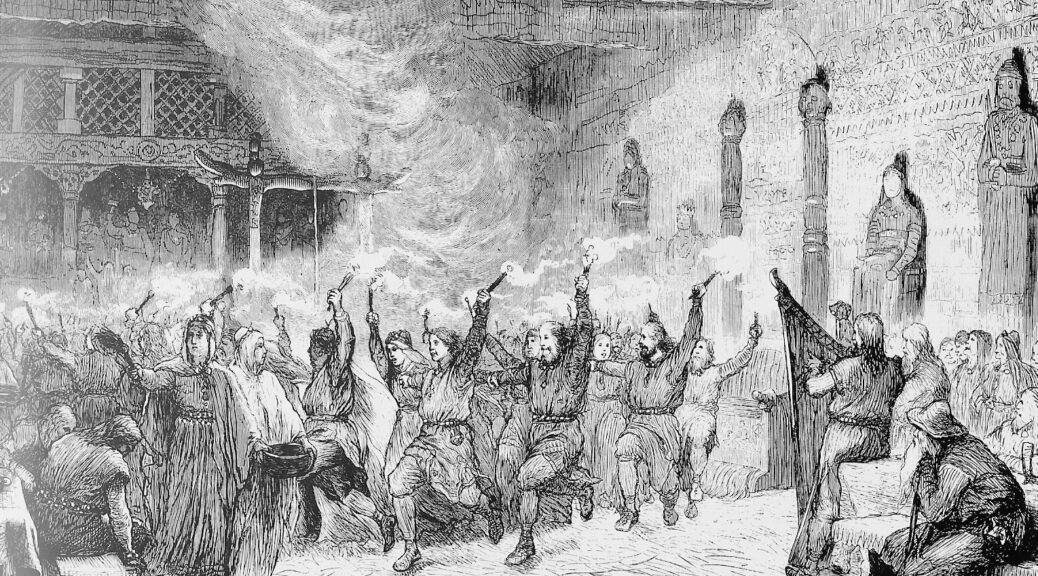

People lit bonfires to honor the dísir and to provide light and warmth. People also lit fires to ward off evil spirits and diseases. Our ancestors considered the smoke and ashes sacred, and sometimes used them for divination or healing.

Music, dance, and poetry were also integral to Dísablót. Singing and playing instruments were ways people praised and thanked the dísir, as well as expressing joy and gratitude for spring’s arrival. The bards and skalds, who were the Norse poets and storytellers, recited epic tales and sagas of the gods and heroes.

Dísablót was also a time for socializing and feasting. The participants, who could be family members, friends, or neighbors, shared the offerings and the food, and drank together. This communal aspect of Dísablót reflected the importance of kinship and community bonds in Norse society.

Dísablót in Modern Times

Although the practice of Dísablót ceased with the Christianization of Scandinavia in the Middle Ages, the memory and legacy of this festival have survived and been revived in modern times. Contemporary heathen and pagan communities have adapted and reinterpreted the rituals and meanings of Dísablót to fit their own beliefs and practices. Some groups hold public or private ceremonies that follow the traditional format of offering food, lighting fires, and reciting poetry. Others create their own variations that incorporate elements of personal spirituality or social activism.

Dísablót has also become a symbol of Norse identity and heritage. Some Scandinavian countries, such as Sweden and Iceland, have incorporated Dísablót into their cultural calendars as a way of preserving and promoting their historical traditions. Museums, festivals, and educational programs feature Dísablót as a way of educating the public about the pre-Christian past and the continuity of cultural values.

Moreover, Dísablót has gained popularity and recognition among non-Scandinavian pagans and heathens as a way of connecting with their ancestral roots and honoring the feminine divine. As the dísir represent a diverse range of female energies and archetypes, they are seen as a source of inspiration and empowerment for women and queer people. Dísablót, therefore, has taken on new meanings and significance for those who seek to reclaim their spiritual heritage and resist the dominant norms of patriarchal monotheism.

A Significant Holiday Worth Celebrating

Dísablót is a fascinating and rich festival that reflects the complex and diverse religious and cultural landscape of ancient Scandinavia. Its emphasis on fertility, ancestor worship, communal bonds, and artistic expression has resonated with people throughout history and across borders. Dísablót offers a valuable opportunity to explore and celebrate the feminine divine, the cycles of nature, and the power of community.

—

Did you know you can become my patron for as little as $5 a month? This entitles you to content not posted anywhere else. Plus you get to see posts like this three days before the public! Without patrons, I’d be having a very hard time keeping this blog going. Become a patron today!Become a Patron!

All right, buckle up, fellow pagans and Heathens, because it’s time to talk about the elephant in the room: Easter. You know, that holiday where Christians celebrate the resurrection of their lord and savior Jesus Christ by painting eggs, eating chocolate bunnies, and hiding baskets of treats for their kids? Yeah, that one.

All right, buckle up, fellow pagans and Heathens, because it’s time to talk about the elephant in the room: Easter. You know, that holiday where Christians celebrate the resurrection of their lord and savior Jesus Christ by painting eggs, eating chocolate bunnies, and hiding baskets of treats for their kids? Yeah, that one. Let’s start with the name itself: Easter. You might be surprised to learn that it’s actually named after a pagan goddess, Eostre (or Ostara), who was worshipped by the Germanic peoples of Europe. She was associated with the spring equinox, fertility, and new beginnings – which makes sense, considering that spring is the time when the world wakes up from its winter slumber and everything starts to bloom and grow again.

Let’s start with the name itself: Easter. You might be surprised to learn that it’s actually named after a pagan goddess, Eostre (or Ostara), who was worshipped by the Germanic peoples of Europe. She was associated with the spring equinox, fertility, and new beginnings – which makes sense, considering that spring is the time when the world wakes up from its winter slumber and everything starts to bloom and grow again.

But let’s move on to some of the more tangible trappings of Easter. Eggs, for example. The egg is a potent symbol of fertility and new life in many cultures. Eggs have been used in springtime celebrations for thousands of years.

But let’s move on to some of the more tangible trappings of Easter. Eggs, for example. The egg is a potent symbol of fertility and new life in many cultures. Eggs have been used in springtime celebrations for thousands of years. Let’s now look at the Easter bunny. This fluffy little creature has nothing to do with the resurrection of Jesus Christ, but everything to do with the pagan celebration of spring. In Germanic folklore, the hare was associated with the goddess Ēostre, and was seen as a symbol of fertility and new life. The tradition of the Easter bunny laying eggs (yes, you read that right) is thought to have originated in Germany, where children would make nests for the hare to lay its eggs in.

Let’s now look at the Easter bunny. This fluffy little creature has nothing to do with the resurrection of Jesus Christ, but everything to do with the pagan celebration of spring. In Germanic folklore, the hare was associated with the goddess Ēostre, and was seen as a symbol of fertility and new life. The tradition of the Easter bunny laying eggs (yes, you read that right) is thought to have originated in Germany, where children would make nests for the hare to lay its eggs in.

Here in the Northern Rockies, harvest is in full swing. Lots of peppers, corn, beans, potatoes, melons, and pumpkins fill the farmer’s markets. Inevitably, that means food banks get a ridiculous amount of produce donated from local farms.

Here in the Northern Rockies, harvest is in full swing. Lots of peppers, corn, beans, potatoes, melons, and pumpkins fill the farmer’s markets. Inevitably, that means food banks get a ridiculous amount of produce donated from local farms.  I won’t bore you with my shopping experience, but suffice to say, most of the food had been picked over early. That being said, as I waited, stuff that I actually needed appeared and I was able to bring home a lot of good stuff.

I won’t bore you with my shopping experience, but suffice to say, most of the food had been picked over early. That being said, as I waited, stuff that I actually needed appeared and I was able to bring home a lot of good stuff. Our ancestors needed to prepare for the lean winter months. That required them to pay attention to the harvest. Harvest was a time when everyone worked, from the highest thegn to the lowest slave. Landowners at least had to supervise the harvest and keep track of everything being done, if they wanted it done correctly. Women and children had to help process the food to ensure it was properly preserved.

Our ancestors needed to prepare for the lean winter months. That required them to pay attention to the harvest. Harvest was a time when everyone worked, from the highest thegn to the lowest slave. Landowners at least had to supervise the harvest and keep track of everything being done, if they wanted it done correctly. Women and children had to help process the food to ensure it was properly preserved. If you were a lord, you might have delegated oversight to trusted men or women, but this depended on how much land you owned, what time in history you lived, and how big your kindred was. Remember, kindreds were basically extended family. There might be people whom you had no famillial ties within your village, but they and their families had some positive aspects for being considered part of your kindred.

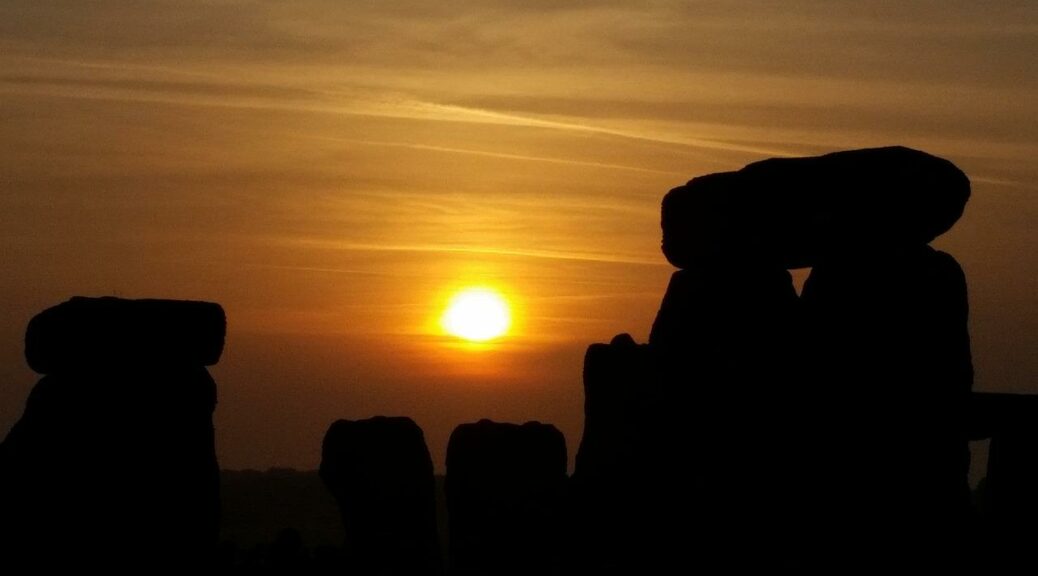

If you were a lord, you might have delegated oversight to trusted men or women, but this depended on how much land you owned, what time in history you lived, and how big your kindred was. Remember, kindreds were basically extended family. There might be people whom you had no famillial ties within your village, but they and their families had some positive aspects for being considered part of your kindred. Winter, for all its beauty and majesty, could be a very brutal time for kindreds. Basically if you didn’t have the food saved, you were shit out of luck. Sure, there was game and fish to be had–assuming you could break a hole in the ice or find game in the snow–but other than your livestock and your food stores, that was it when it came to edible foods. The northern hemisphere was retreating into darkness, culminating in the solstice where the light returned.

Winter, for all its beauty and majesty, could be a very brutal time for kindreds. Basically if you didn’t have the food saved, you were shit out of luck. Sure, there was game and fish to be had–assuming you could break a hole in the ice or find game in the snow–but other than your livestock and your food stores, that was it when it came to edible foods. The northern hemisphere was retreating into darkness, culminating in the solstice where the light returned.  The gods help you if you had raiders, thieves, pests, or a bad harvest. There’s a reason why our ancestors were good warriors. They had to be. Not only did they raid other peoples for their treasures, but they also had to defend their homes against other raiders. Losing your food was a death sentence, unless you somehow procured more. This is why it was so important to be part of a kindred and not an outlaw. Outlaws didn’t have the safety of a kindred.

The gods help you if you had raiders, thieves, pests, or a bad harvest. There’s a reason why our ancestors were good warriors. They had to be. Not only did they raid other peoples for their treasures, but they also had to defend their homes against other raiders. Losing your food was a death sentence, unless you somehow procured more. This is why it was so important to be part of a kindred and not an outlaw. Outlaws didn’t have the safety of a kindred. Now with the harvest almost completed, we modern day Heathens can look to have a harvest festival now. Maybe it’s winter finding, Alfarblot, or Samhain for you. Maybe you just want to celebrate Harvest. That’s perfectly acceptable. Maybe you’ve had a rough year and need something to look forward to. Maybe you had a good year and need to celebrate it. As a Heathen, the second harvest festival seems like a good idea.

Now with the harvest almost completed, we modern day Heathens can look to have a harvest festival now. Maybe it’s winter finding, Alfarblot, or Samhain for you. Maybe you just want to celebrate Harvest. That’s perfectly acceptable. Maybe you’ve had a rough year and need something to look forward to. Maybe you had a good year and need to celebrate it. As a Heathen, the second harvest festival seems like a good idea. Our ancestors celebrated a holiday known as Alfarblot. It was to remember our male ancestors. When it was celebrated exactly, we don’t know, but I seem to recall it could have been in the fall or the winter. Choosing to remember our male ancestors during the second harvest festival seems appropriate. So, if you want to celebrate Alfarblot around Halloween or Samhain, that’s perfectly okay. I like to think of it around the beginning of November, but anytime around Halloween is fine. Seeing as we really don’t know all the holidays from the past, we can celebrate it in the spirit as it was intended.

Our ancestors celebrated a holiday known as Alfarblot. It was to remember our male ancestors. When it was celebrated exactly, we don’t know, but I seem to recall it could have been in the fall or the winter. Choosing to remember our male ancestors during the second harvest festival seems appropriate. So, if you want to celebrate Alfarblot around Halloween or Samhain, that’s perfectly okay. I like to think of it around the beginning of November, but anytime around Halloween is fine. Seeing as we really don’t know all the holidays from the past, we can celebrate it in the spirit as it was intended. Harvest is a time for celebration of the foods we’ve received from our farmers, but more importantly, the Earth. Just think how our lives would be different if we couldn’t grow fruits and vegetables. As a species, we all might still be hunter/gatherers. Or maybe we wouldn’t even exist because the carrying capacity of the land wouldn’t be able to support so many humans.

Harvest is a time for celebration of the foods we’ve received from our farmers, but more importantly, the Earth. Just think how our lives would be different if we couldn’t grow fruits and vegetables. As a species, we all might still be hunter/gatherers. Or maybe we wouldn’t even exist because the carrying capacity of the land wouldn’t be able to support so many humans. If you’re looking for ways to celebrate the harvest, here are some tips:

If you’re looking for ways to celebrate the harvest, here are some tips:

We’re coming up on August 1st, which is the August Harvest Festival, Hlæfæst. It’s also known to most modern pagans as Lammas. If you’re still using the AFA Holiday wheel-of-the-year, it’s called

We’re coming up on August 1st, which is the August Harvest Festival, Hlæfæst. It’s also known to most modern pagans as Lammas. If you’re still using the AFA Holiday wheel-of-the-year, it’s called  Although Lammas celebrates a god from the Celtic pantheon, there’s no reason why we can’t appropriate it and call it Hlæfæst. Hlæfæst celebrates the grain harvest, which honors Sif, Thor, Freyr, and Freyja. Rather than just honor Freyr with Freyfaxi, I think honoring four gods and goddesses is better because these are the gods who make the grain grow. It makes sense to give thanks to them.

Although Lammas celebrates a god from the Celtic pantheon, there’s no reason why we can’t appropriate it and call it Hlæfæst. Hlæfæst celebrates the grain harvest, which honors Sif, Thor, Freyr, and Freyja. Rather than just honor Freyr with Freyfaxi, I think honoring four gods and goddesses is better because these are the gods who make the grain grow. It makes sense to give thanks to them.